By Jenny Vincent & David Shultz

18 months after the catastrophic derailment of a train carrying hazardous materials in East Palestine, Ohio, Jenny Vincent and David Shultz outline how crisis communications can be transformed into a more robust and comprehensive information architecture.

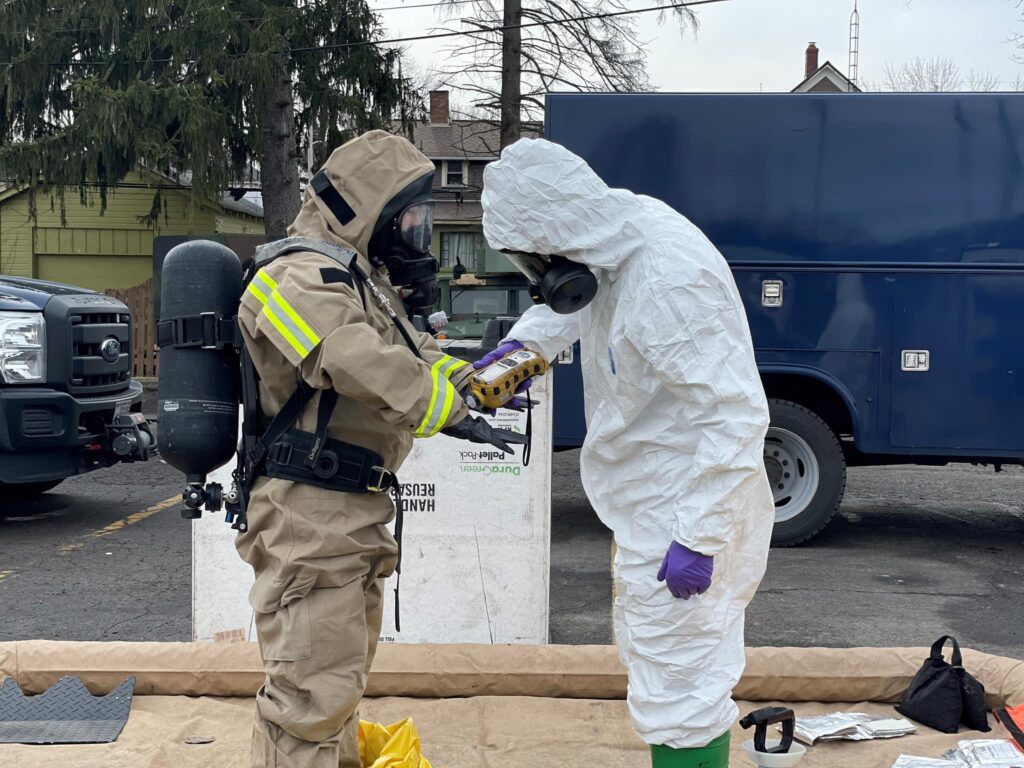

On February 3, 2023, a train derailed in East Palestine, Ohio, carrying hazardous and non-hazardous materials. A total of 38 freight cars derailed and three of those freight cars carrying flammable liquids were fractured during the accident and caught fire. A one-mile initial exclusion area was established around the fire at the derailment site. Five additional derailed tank cars were identified as carrying a compressed liquified flammable gas named vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) and were not ruptured during the accident. However, four of these cars holding VCM were exposed to fires from those three burning freight cars.

As a result of the fires threatening the VCM cars, the incident commander expanded the exclusion radius to two miles and decided to conduct a vent and burn procedure on the VCM cars. The National Transportation Safety Board investigation discovered Norfolk Southern, the railroad company, was given information about the VCM from the shipper explaining that the VCM had stabilizers and that the fires from the ruptured rail cars did not pose a threat to the chemicals inside the VCM cars. However, the incident commander was not provided the information from the VCM shipper. Furthermore, exchanges between the public, government, and first responders were inefficient and lacked relevant information hampering response efforts and stirring sentiments of distrust towards authorities. For example, citizens’ claims of dead fish due to contaminated waters caused by the burning cars were not addressed and increased tensions between citizens and authorities.

Information exchange in a crisis is critical to establishing a protective perimeter, mitigating further damage, and resolving issues to stabilize the emergency. However, effective crisis communications are elusive to modern United States emergency response efforts. Poor communication cripples decision-making efforts by acting as a filter for critical information while also isolating first responders and authorities from the citizens they are protecting. Today we must resolve these communications issues to protect both our citizens and our first responders. Technology offers tools to build information exchange processes with capacity to support a crisis like we experienced in East Palestine. Technology will not solve all our communication challenges, but it can certainly help to improve information flows and exchanges to improve decision-making in a crisis.We suggest transforming our understanding of communications during a crisis from a skillset or task to infrastructure, similar to a system of fire hydrants. As a fire hydrant is a function of a city’s water infrastructure, emergency communications must become a function of a city’s communication and information architecture to meet the demands encompassed today. This transformation of our understanding also recognizes the investment and work required to design, test, and implement an emergency communications network capable to effectively transform the United States’ ability to respond to crisis.

Transforming Chaos into Process

The major hurdles to overcome at the outset of a crisis are to convert unknowns to knowns and to establish an effective perimeter and mitigate further damages. Technology offers tools to create information pathways from citizens to command centers where critical information can be analyzed, prioritized, and visualized in a manner to rapidly build situational awareness for both the community and the command center. This approach converts citizen reporting and concerns into useful and relevant information to capture the unknowns, establish effective perimeters, and mobilize limited resources. In one example, mobile ArcGIS forms provide a process for local citizens to share reports and photos with local authorities on a common information layer. In the East Palestine example, citizens may report dead animals, contaminated water, blocked egress routes, accumulation of smoke debris, and other information relevant to emergency management response.

In East Palestine and surrounding counties, citizens did not have a clear mechanism to communicate details to the incident commander, and the incident commander did not have a clear mechanism to ensure all citizens received critical information. Applying technology to create an emergency communications infrastructure ensures that the incident commander gains access to critical information. This same infrastructure supports citizens with information that they need in order to follow specific instructions and make decisions for their home and family.

Imagine local citizens with the ability to share reports of contaminated water using forms on a mobile application which feeds into the emergency communications information architecture to analyze, visualize, and provide updates or instructions back to citizens. This same infrastructure can support local authorities to allocate limited resources and follow up with citizens as needed. As the crisis continues this data can be applied to hazard modeling, environmental surveys and sampling, and evacuation planning. A well-designed emergency communications information infrastructure plan will transform the chaos caused by poor communication into a rich resource to greatly improve our emergency response operations and protect our citizens and critical infrastructure.

Transforming Data into Flight Controls

A chemical release model informs evacuation distances and supports contingency planning. Typically, the model drives the planning and once the plan is initiated there is no turning back and no “in-flight” adjustments. The model is the bow, and the plan is the arrow. Whatever decisions and actions are made during emergency response become part of consequence management. However, information processing tools can transform our emergency response operations from bows and arrows to a state-of-the-art flight control deck with real-time information providing the instrumentation to help guide the plan.

An emergency communication information infrastructure integrated with local environmental data and reporting provides a mechanism where data analysis and visualization can effectively inform local authorities conducting emergency planning and operations. For example, a hazard model can be either validated or invalid based on changes in weather or other unforeseen circumstances. Integrating real-time data during an emergency response operation provides agility to the incident command center to respond to changes in the scenario and take appropriate actions to mitigate damages. Likewise, this capability can also keep citizens informed of obstructions causing evacuation delays or updating evacuation routes in real-time based on circumstances.

The key advantage that technology provides to information processing during a crisis is to create processes and flows for information. Our communities have several types of infrastructure including transportation, energy, and water. We must think of crisis communications as requiring an information architecture that gathers, sorts, and shares information to help protect the community. Imagine a fire truck with no fire hydrants available in a community. An information architecture provides an organized infrastructure to effectively manage an emergency and builds resilience and trust in our local communities.

Transforming Communication into Data

What would this information architecture look like? The development of an information architecture should incorporate best practices of crisis communication and must clearly address data culture.

Balancing timeliness and accuracy: For example, crisis response requires collection and dissemination of information as it becomes available. This information is often incomplete at the time of use and reporting. Traditional ways to receive this information often limit its use across stakeholders due to system access and compatibility.

Data architecture can improve the timeliness of information dissemination to the right experts at the right time across the multi-functional response teams using roles-based access. In this instance, experts across different teams can collaborate in real time inside the data, and coupled with their training and expertise can better inform their next actions. Also, the ability to connect a time stamp to a piece of data, as well as other meta data such as collection details and geo-location, can reduce uncertainty and increase accuracy. By creating this system of agnostic architecture to share emerging data across multi-functional response teams (e.g. local, state, federal authorities; industry; subject matter experts), the various response elements will gain more rapid insights into current conditions.

Providing transparency while addressing uncertainty: a key best practice of crisis communication is to provide updates to the affected community at regular and frequent intervals, and when appropriate, as pertinent details become available. This same data can be curated and transformed into community messaging at the societal and at the individual level. For example, a clean wastewater sample collected on Monday does not mean that the same wastewater is consumable on Tuesday. Just as data architecture can improve timeliness of information dissemination to the right experts at the right time, in this example the methodology and frequency or schedule that wastewater will be sampled and the resulting reports of the water contamination levels can be assigned to affected populations. Additionally, linking multiple resources, experts can apply industry standards and communicate those methodologies of testing and the resulting reports within this data architecture.

Facilitate bi-directional information sharing: it is not enough to merely disseminate this data to first responder networks and the community. By establishing bi-directional data sharing mechanisms, data maturity, data cleaning, and data analysis can more rapidly advance situational understanding across this common operating picture. Furthermore, applying warnings and notifications as new data is added or new thresholds are reached can help data consumers more rapidly sift through the large amount of information being ingested.

Accessibility and consistency: the internet has clearly changed the way we consume data. For example, in only a four-year span, the Pew Research Center in a U.S. survey found adults’ preference for receiving news from television was only 27%, having dropped by 8% from 2020 to 2023, while digital device preference for media sources rose by 6% to 58% in the same period.

Also, the internet and mobile phones in particular have provided a new way to share and communicate information in real-time and at any location. A successful platform for transforming public communication into data for first responders should focus on readily available technology interfaces (e.g. mobile phone & downloadable apps). Data input should include geo-location, time stamp of data entry, and a unique identifier (e.g. tracking code) so both the response team and citizens can engage one another with follow-on questions, dialogue, and notification of actions taken, as applicable.

Building trust: with an effective data architecture the incident commander gains the ability to point back to data, response efforts can increase the transparency and defensibility of decisions and actions, and increase trust, all without adding a burden on the response teams to build custom tools to collect and log actions and information. Trust is critical to a successful emergency response capability and operation. Emergency responders from government and industry must trust their training, leadership, and equipment to effectively respond to a crisis.

Additionally, emergency responders must also have the trust of the people they are protecting in a crisis to be effective. When distrust grows both the emergency responder and citizen are at greater danger. Technology can help to build trust in a crisis by providing an easy and effective way for citizens to communicate reports and questions to emergency responders, and for emergency responders to incorporate these reports and questions into a crisis response. Furthermore, creating multi-direction and two-way communication channels to inform citizens of actions being taken and to share findings and announcements in near-real-time using easy-to-comprehend visualizations will build trust over time and keep everyone informed.

Today our citizens face a wide variety of threats. Our incident commanders and citizens require these capabilities, and we have the technology to fill these gaps. It is our opportunity and responsibility to bring these capabilities to the community and first responders to provide the best possible response outcomes, and in doing so, we will increase the trust that is so critical in times of crisis.

Transforming Information Infrastructure to Support Emergency Response

Just as critical to emergency response as fire hydrants, 911 and police dispatch processes is an information architecture. A useful information architecture will enable local authorities to collect and analyze reporting from citizens, first responders, and partners in an organized process to inform decision making and communicate with citizens. This sort of work requires investment towards building an emergency communications information architecture as a function of our nation’s current communications architecture to collect information, conduct analysis of the data, and produce visualizations helpful to incident command centers and local populations.

Technology will not solve all the issues our nation is currently experiencing in crisis response and emergency management operations, but it will provide a foundation to modernize emergency management to increase the effectiveness of response to crises across our all our nation’s local governments.

Jenny Vincent is a Lead Associate with Booz Allen Hamilton focused on developing integrated and data driven solutions to counter weapons of mass destruction (CWMD). Jenny is a Strategy Consultant with 17 years’ experience overseeing dynamic, multi-functional technical teams as project and program manager, with eight of those years supporting DoD clients in the Indo-Pacific, and the past six dedicated to the CWMD mission set. Jenny’s priority is integration of emerging technologies and information across the emergency management and CWMD landscape. She holds a Bachelor’s in Psychology with a minor in Medical Humanities from Baylor University, an M.B.A. from Oklahoma City University, and a Graduate Certification in Biodefense from George Mason University.

David Shultz is a Lead Associate with Booz Allen Hamilton focused on developing solutions to counter weapons of mass destruction (CWMD). David served 26 years in the United States Navy Explosive Ordnance Disposal community and has supported the CWMD mission sets in industry the past eight years. David’s priority interest is the protection of United States military and citizens from WMD threats and he works along the seam of emerging technologies to support people in this mission space.