By Andy Oppenheimer, former editor, CBNW

How should we handle a nerve agent attack? Andy Oppenheimer looks back on the 2018 Novichok attacks in Salisbury and examines future challenges and possible responses if another similar incident should happen in the future.

In the ever-challenging field of CBRN weapons and defence, we have long been concerned by the threat of chemical weapons’ use by terrorist groups and lone actors, especially since 9/11 and more recently, the Islamic State (ISIS). However, so far nation-states have been the perpetrators: most notable incidents are Syria’s 300 bombardments of sarin and chlorine on its own people between 2013 and 2018 and Russia’s use of the nerve agent Novichok to assassinate or attempt to kill opponents of the regime.

Given that Russia is an increasingly hostile threat to the West, since its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and NATO’s growing involvement in the war, there are fears that its totalitarian and ruthless leader will deploy chemical weapons in that theatre. Regardless, the overwhelming evidence of Russia’s prior use of chemical weapons to target individuals deemed to be enemies of the Russian state is the focus of this article.

The latest Novichok target

Most recently, Novichok is suspected to have been used against Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny, who became seriously ill on a flight from Tomsk, Russia to Moscow on 20 August 2020. It was suspected that the nerve agent was slipped into a cup of tea at Tomsk airport. In addition, a German laboratory found traces of Novichok on a bottle of water in his Tomsk hotel room.

Navalny was treated in Omsk for three days before being put into a medically induced coma in The Charité Hospital in Berlin. He began a protracted recovery after he woke from coma on 7 September. Toxicology tests carried out in military laboratories in France and Sweden confirmed suspicions by German doctors treating him that a form of Novichok has been used.

Novichok: top of the scale

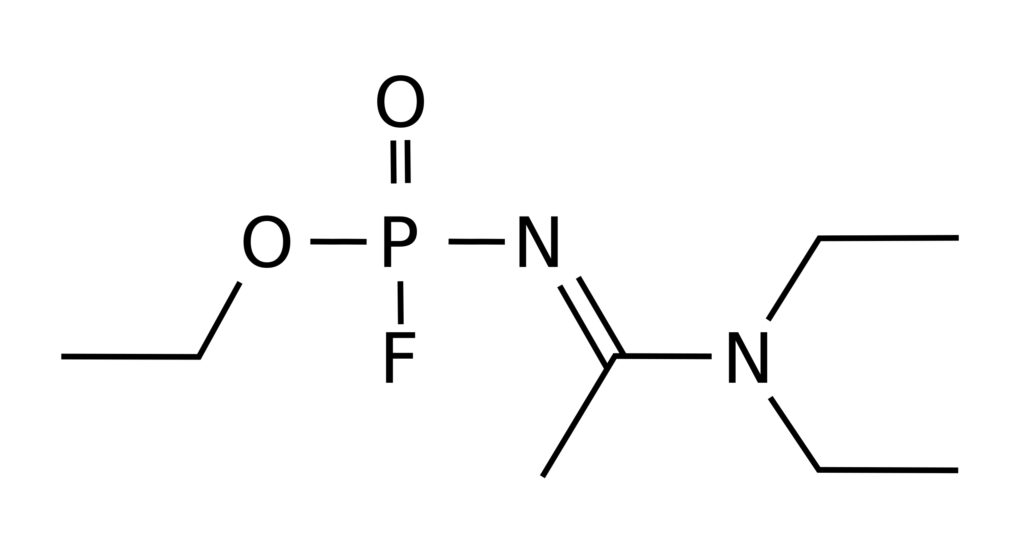

Novichok (‘newcomer’ in Russian) can be liquid or solid, dispersed as an ultra-fine powder. The symptoms can develop as rapidly as within 30 seconds of contact. It acts by inhibiting the enzyme cholinesterase, triggering the body’s muscles into overdrive, including those controlling respiration. The Novichok group is believed to be eight times more toxic than VX, itself the most toxic of nerve agents that includes sarin, tabun and soman.

Absorption may also occur via the skin or mucous membranes, as in the Salisbury Skripal cases described below, however, dermal absorption produces a slower build-up of symptoms.

Novichok agents are known to have been developed secretly by the Soviet Union in the 1970s at the Shikhany military research establishment in central Russia, chiefly to evade normal chemical detection techniques and to penetrate chemical protection equipment on the battlefield.

Salisbury 2018: the Skripals

The most notorious example of Novichok use, specifically, to eliminate a Russian spy working for the British, took place on British soil, but failed. Then a further incident resulted in the death of a British citizen, who had nothing to do with spying.

To recap: on 4 March 2018, former Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) agent and retired Russian military intelligence officer Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia became critically ill in Salisbury, Wiltshire. The poison was later identified in samples as A234, a military-grade nerve agent, by the UK’s prime chemical weapons research centre, the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) at nearby Porton Down.

Traces of the nerve agent have been smeared on the door handle of the Skripal home. The Skripals were found unconscious and foaming at the mouth on a park bench by a member of the public at the town’s main shopping centre. A police officer attending the crime scene, Detective Sergeant Nick Bailey also fell seriously ill. The three victims eventually recovered after receiving unprecedented intensive care at Salisbury General Hospital.

Salisbury: Dawn Sturgess

Several months later, on 30 June, an innocent passer-by, Dawn Sturgess was exposed to the same nerve agent by handling a contaminated item – a perfume bottle – and fell ill in Amesbury, some eight miles from Salisbury. She died in hospital nine days later. Her partner, Charlie Rowley also became critically ill, but recovered and was discharged on 20 July 2018. The long-term effects of the nerve agent on the future health of those who have recovered will be under scrutiny for years to come.

The attack injured four citizens other than the intended targets in a small town popular with tourists. It caused millions of pounds worth of damage to property and the local economy. Many sites were cordoned off for several weeks, including locations visited by the Skripals following Yulia’s arrival in the UK, including a restaurant, a pub, a car park, a cemetery where relatives are buried, nearby streets, as well as the Skripals’ car.

Operation Morlop

The Salisbury incidents prompted a massive first-response operation at the scene of the crime and its environs, including world-class chemical weapons specialists from Dstl. More than 200 counter-terrorism officers worked on one of the most complicated UK investigations, examining 5,000 hours of CCTV footage and 1,350 seized items.

British Army and Royal Air Force (RAF) personnel were deployed in support of government departments and civil authorities conducting the recovery operation. Operation Morlop involved personnel from Suffolk-based 20 Wing RAF Regiment while the Wiltshire-based 22 Engineer Regiment worked in the surrounding area to remove material under direction of the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Hundreds of military personnel from the British Army, Royal Marines and RAF were deployed to the town, including instructors from the Defence CBRN Centre and the 29 Explosive Ordnance Group. Fuchs decontamination vehicles were used in an unprecedented operation to tow away cars and ambulances that could have been contaminated. These decontamination vehicles also served as mobile laboratories.

Personnel from the Falcon Area Survey & Reconnaissance Squadron were deployed as the British Army’s only mounted counter-CBRN unit, a sub-unit of the 22 Engineer Regiment. All experts involved had to work long hours in heavy protective suits during an especially hot summer.

Future response

The Salisbury attacks led to greater knowledge about Novichok agents and the way to treat victims. However, NHS hospitals have long had protocols for dealing with contaminated casualties, so Salisbury District Hospital was geared up, in addition for being prepared for a potential accident at Dstl.

By March 2019, one whole year later, the clean-up of affected areas of Salisbury had been completed. The effectiveness of the massive decontamination operation prevented thousands more potential deaths and casualties in the town.

In 2018, for some time the medical teams could not identify the causative agent and treated the patients on the basis of instinct and intuition. What they learned would be paramount in a future incident: rapid administration of atropine, now carried in all UK ambulances, in addition to pralidoxime and diazepam (anticonvulsant).

Decontamination could be rapidly carried out to remove the agent and prevent additional exposure to carers and others. Anyone affected should wash their skin with soap and water, which despite its simplicity is effective against nerve agents. Eyes should be irrigated thoroughly for at least ten minutes.

Future challenges

The multi-agency response, however, was launched long before the coronavirus pandemic. If an incident like Salisbury would happen again, it will occur after 13 years of cuts in the health service and military, a protracted pandemic, and with unfilled public sector vacancies. The Salisbury attacks tested the first-responder, military and hospital services to the limit. With increasing pressure on all responders and other authorities, acts of chemical terrorism on targeted individuals in the UK at least could be viewed as the last straw.

In September 2020, Navalny was said to be still unable to use a phone, pour water into a glass, or go up or down steps without his legs trembling. Now imprisoned in Russia, the long-term effects of his poisoning are unknown. His plight is a poignant reminder that even when a victim of Novichok survives, they face a long road ahead to regain anything resembling a normal life.

About the Author:

Andy Oppenheimer is author of IRA: The Bombs and the Bullets – A History of Deadly Ingenuity (2008) and a former editor of CBNW and Jane’s NBC Defense. He is a Member of the International Association of Bomb Technicians & Investigators and an Associate Member of the Institute of Explosives Engineers and has written and lectured on the IRA since 2002.

*Copyright for heading picture ©SkyNews