By Yan Cavalluzzi

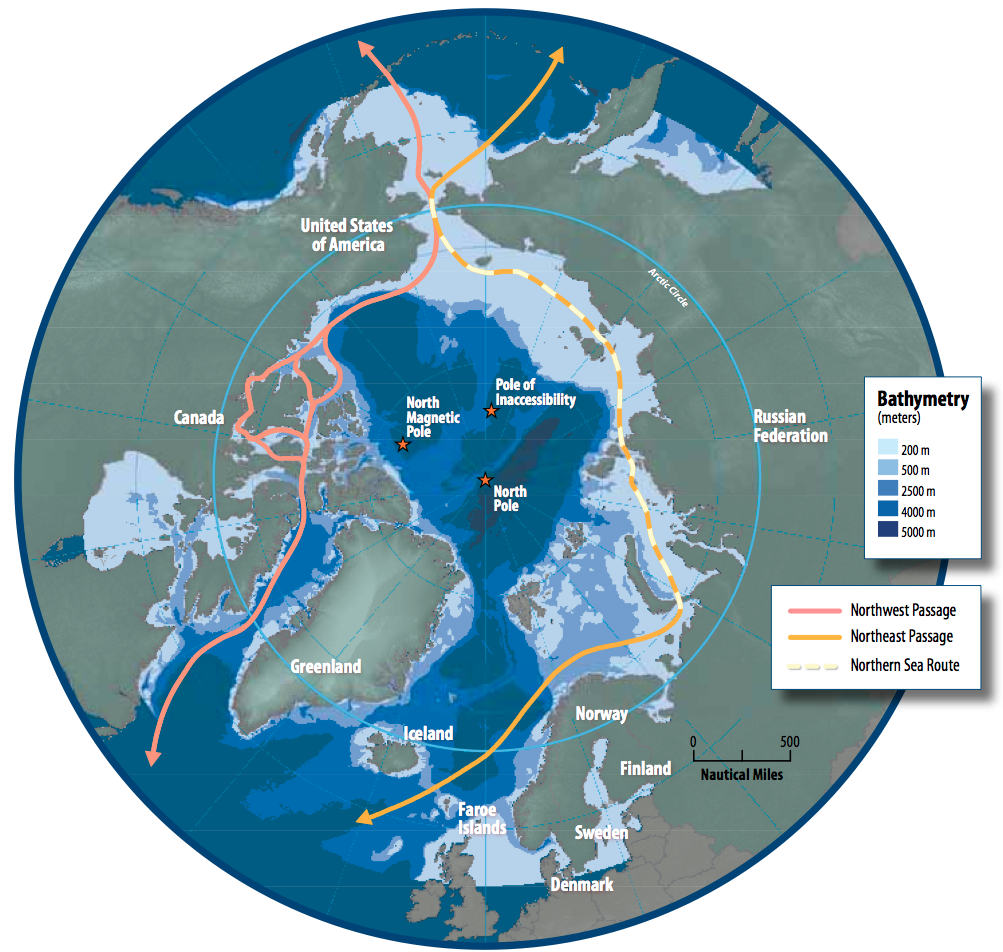

As the ice retreats in the Arctic Sea, the Northern Sea Route (NSR) — the coastal passage along Russia’s northern shore — has shifted from a seasonal passage to a strategic hinge for trade, energy, and security. However the stakes are not merely commercial. The Arctic is thought to contain ~13% of the world’s undiscovered oil and ~30% of its undiscovered natural gas, which helps explain the region’s pull-ongovernments and corporations despite high operational risk). At the same time, Russia controls roughly 53% of the Arctic Ocean coastline, giving Moscow unusual leverage over routes and infrastructure.

This leverage is embedded in national strategy. President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly described the Arctic as central to Russia’s future — “The Arctic is a region of great importance; it will provide for the future of our Russia” — and has matched the rhetoric with sustained investment in icebreaking capacity, ports, and military basing. From a CBRN standpoint, the key takeaway is straightforward: the NSR is opening in the shadow of Russia’s sea-based nuclear deterrent on the Kola Peninsula. That proximity makes the NSR a dual-use corridor where commercial flows must be carefully deconflicted with the requirements of a sea-based nuclear force and with the realities of radiological/nuclear (RN) risk management in remote, high-latitude conditions.

UNCLOS note. Leveraging ambiguities in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, Moscow has sought The Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) recognition of an extended Arctic continental shelf by arguing that the Lomonosov and Mendeleev ridges are natural prolongations of the Eurasian landmass—thereby enlarging Russia’s exclusive economic rights over seabed resources and reinforcing control along northern routes. The CLCS has not endorsed Russia’s submissions in full, requesting further documentation and leaving key portions disputed—underscoring the Kremlin’s intent to cast itself as the dominant Arctic authority even when international acceptance is partial.

© Author as listed (often Hannes Grobe/AWI) on Wikimedia Commons — CC BY-SA 3.0/4.0

Hydrocarbons and the commercial pull

The USGS Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal remains the baseline: about 90 billion barrels of oil, 1,669 trillion cubic feet of gas, and ~44 billion barrels of natural-gas liquids likely remain in the region, largely offshore in relatively shallow waters. Much of the gas endowment aligns with Russia’s Yamal–Gydan projects, which already ship LNG to Europe and Asia. Regardless of the global energy transition’s pace, these reserves will continue to influence investment decisions, logistics planning, and national strategies for energy security.

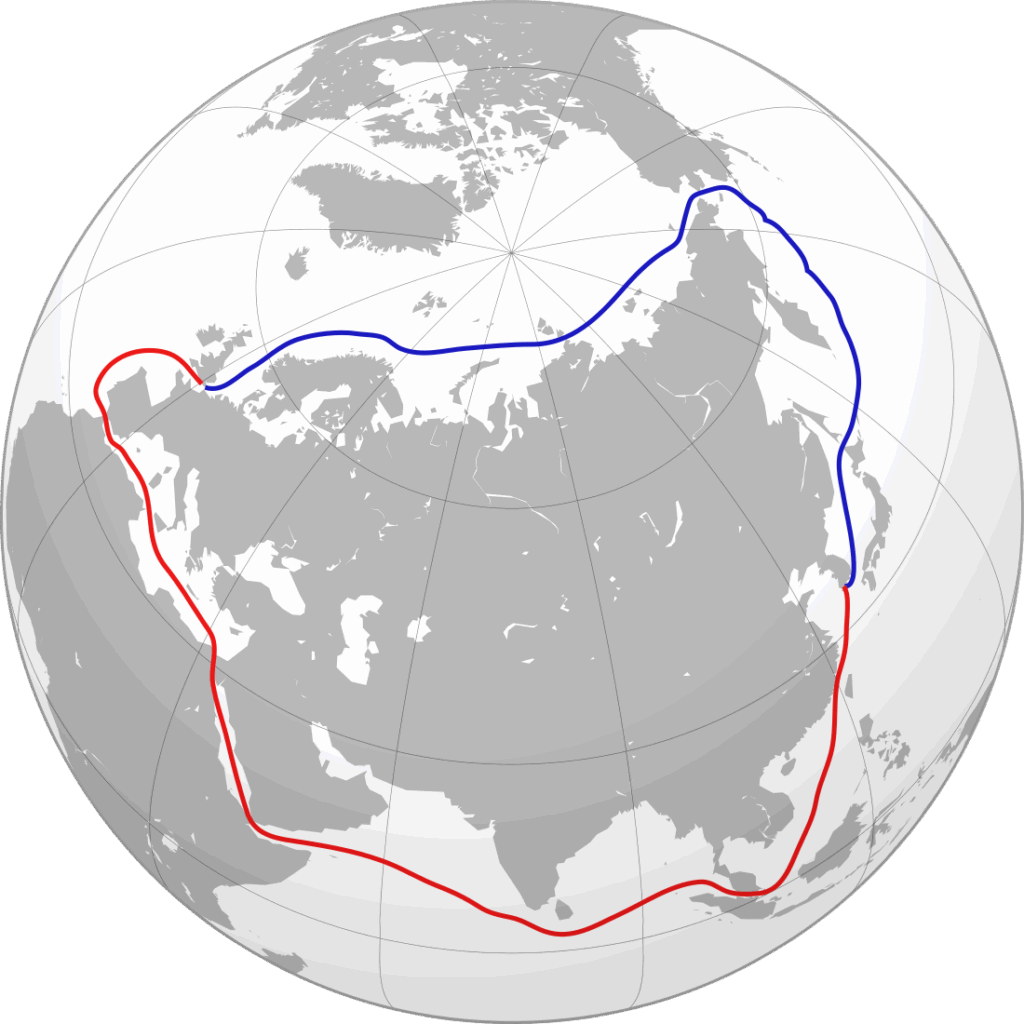

On the maritime side, stylized comparisons show the NSR can cut Europe–Northeast Asia distances by roughly 40%versus the Suez route, saving up to two weeks at sea when ice and weather cooperate. Those savings are not uniformly available — ice dynamics, insurance, and seasonal constraints still matter — but they are large enough to draw periodic interest from carriers, energy major players, and commodity traders looking to arbitrage time, fuel, and risk exposure.

In practice, NSR traffic is still led by origin-or-destination Arctic shipments (energy and bulk), yet volumes are rising. Rosatom reported ~36.3 million tonnes in 2023 and ~37.8–37.9 million tonnes in 2024, including a record 92 through-transits, a significant growth over a decade, even if tiny compared to Suez. A headline moment came in January 2021, when three Arc7 LNG carriers completed a full winter transit without icebreaker escort. None of this makes year-round liner schedules routine, but capability and ambition are clearly advancing in tandem.

For CBRN planners, these numbers matter less as trade trivia and more as exposure indicators: more hulls, more people, and more complex cargoes in a harsh environment where emergency response is logistically demanding and where RN-sensitive assets operate nearby. The volume trend is a proxy for the probability of incidents — industrial, navigational, or environmental — that could require rapid, technically competent, and politically delicate responses.

© Author as listed on Wikimedia Commons — CC BY-SA 4.0

The Kola Peninsula and the sea-based leg of Russia’s triad

The most consequential geography for CBRN planners lies just west of the NSR: the Barents Sea and Kola Peninsula, home to Russia’s Northern Fleet. This is the maritime leg of Russia’s nuclear triad, centered on ballistic-missile submarines (SSBNs), now Borei/Borei-A, and backed by nuclear attack submarines (SSNs) Yasen/Yasen-M, for sea denial and long-range strike. The posture follows a “bastion defense” model: layered air and coastal defenses, hardened bases at Severomorsk–Gadzhiyevo–Okolnaya, and under-ice operating areas designed to keep SSBNs survivable for a second strike.

Open sources and satellite imagery have tracked this posture: S-400 deployments (e.g., Novaya Zemlya), runway extensions and new radars at forward bases, and regular live-fire drills that temporarily close large sea areas to civilian traffic. In June 2024, the Northern Fleet conducted missile launches from nuclear-powered submarines during Barents exercises—routine for Russia’s calendar, but a reminder that waters near emerging commercial lanes are nuclear-sensitive.

Why does this matter for the NSR? A thicker flow of commercial vessels does not directly “threaten” SSBN patrols, but it reshapes the operating backdrop. More hulls and more sensors (including commercial satellites, modern navigation suites, and uncrewed systems) produce a denser electromagnetic and acoustic environment. In ice or convoy conditions, the risk of collision or interference rises; in a crisis, the co-location of merchant convoys and sovereign-immune platforms complicates deconfliction, particularly if a civil incident requires swift access near military exclusion areas. The practical takeaway for CBRN planning: a commercial mishap (propulsion failure, cargo fire, fuel spill) can swiftly become a civil-military RN problem in waters Moscow considers strategically intimate. Contingencies need to be scripted in advance, not negotiated on the fly.

From Access to Aftermath: Planning Around Nuclear Icebreakers

Russia’s nuclear-powered icebreakers turn climate windows into predictable convoy movement. The Project 22220 (LK-60Ya) class — Arktika, Sibir, Ural in service; Yakutia fitting out; Chukotka launched; more hulls authorized — provides high-power channel-making through multiyear ice, with dual-draft hulls for deep approaches and shallower estuaries. Plans for the larger Project 10510 (“Rossiya/Lider”) aim to widen channels for heavy tonnage further into winter.

For CBRN readiness, these ships are two things at once: (1) critical winter logistics platforms, and (2) mobile civil nuclear reactors operating in remote, low-infrastructure environments. As winter activity expands, the statistical base for low-probability/high-consequence events — reactor-adjacent fires, groundings in poor visibility, convoy collisions — grows accordingly. Arctic emergency planners (civil and military) therefore need RN-competent SAR playbooks that include convoy vignettes and ice-condition constraints, not just open-water scenarios. Exercises must test radiation monitoring in extreme cold, deployed medical support, decontamination in freezing temperatures, and communications resilience when auroral activity and polar conditions degrade links.

As traffic increases, so does the chance of accidents: even if an incident occurs in international waters, Russia would often be the de facto first responder along much of the NSR, and Moscow has signaled it is uncomfortable with other Arctic states operating close to areas it regards as its own. That political reality should be factored into notification pathways, on-scene coordination assumptions, and public-information plans aimed at avoiding rumor cascades during crisis response.

© Author as listed on Wikimedia Commons — CC BY-SA 4.0

What a busier NSR means for deterrence

The NSR’s growth interacts with the Northern Fleet’s deterrent mission in three ways:

- Mixed-use density raises the odds that an industrial or navigation incident will occur near sensitive patrol areas, forcing civil-military coordination under political time pressure. In such scenarios, knowing in advance who talks to whom, on what circuit, and with what information set can be the difference between a technical resolution and a political standoff.

- The spread of uncrewed and sensor-rich platforms (commercial and governmental) complicates maritime domain awareness and increases the risk that routine data collection is misread as ISR against SSBN patrol boxes. De-risking this space means clarifying flight/operating envelopes, AIS and payload practices, and data-sharing norms where possible.

- Russia’s ability to surge nuclear-icebreaker support for its own logistics gives it operational advantages in winter crises. Others will need Arctic-credible SAR/RN assets — ice-capable hulls, helicopters with cold-weather kits, deployable labs, and assured communications — to avoid over-reliance on Russian assistance in politically charged waters.

- It is unlikely the NSR will replace Suez for mainstream container shipping soon. But selective commercial use, especially LNG and bulk, will continue. The policy challenge for Europe and Asia is to capture real value without importing strategic dependence. That means hardening supply chains that touch the NSR, fielding ice-capable, RN-competent SAR, and institutionalizing incident notification and deconfliction so that mishaps remain technical in their early hours rather than spiraling into politics.

Policy implications for a CBRN-ready Arctic

1) Treat the NSR as an RN-sensitive corridor. Build pre-negotiated incident channels with Arctic neighbors for ice reports, RF interference, and near-misses, linking civil maritime and defense nodes north of Kola. The aim is speed and clarity in the first hours of an event—before uncertainty hardens into accusation.

2) Exercise the nuclear-icebreaker scenario. National or joint drills should include reactor-adjacent fires, convoy collisions in ice, RN sampling in extreme cold, and mass-casualty medical support under polar conditions. Include public-information drills to manage rumor and reassure local communities.

3) Modernize RN legacy monitoring. Regularly repeat joint expeditions to dump sites (e.g., K-27, Stepovogo Fjord), publish data transparently, and keep contingency plans for stabilization or retrieval up to date. Pair scientific campaigns with tabletop exercises that stress-test decision-making if monitoring detects anomalies.

Concluding note. With Finland and Sweden now in NATO, the Alliance’s footprint in the High North has expanded, naturally increasing allied activity — and, with it, some of the ambient tension — in a region already shaped by Russia’s nuclear bastion on Kola. This is another signal that CBRN-related security in the Arctic is serious and tightening, not abstract. As Russia’s Arctic Ambassador-at-Large Nikolai Korchunov warned amid NATO drills, such activity “raises the risk of ‘unintended incidents’, which, in addition to security risks, can also cause serious damage to the Arctic ecosystem.”

Yan Cavalluzzi is the Editor of CBNW Magazine, a CBRNe analyst, and an Arctic security specialist. He cooperates with Canale Energia, writing on the geopolitics of energy. Previously, he served as a Political Advisor during the Italian Navy’s Mare Aperto 2022 exercise, embarked on the aircraft carrier Cavour, where he contributed to operational analysis and doctrine-aligned documentation for senior command.

Yan holds an M.A. in Intelligence and International Security from the Department of War Studies, King’s College London; an M.A. in International Relations; and a B.Sc. in Economics & Business from LUISS Guido Carli.

He has also written for the Centre for Security, Diplomacy and Strategy (CSDS), co-authoring a policy brief on Arctic security, and for Rivista Aeronautica — the Italian Air Force’s official magazine — on the use of drones in CBRN crisis settings.